Fellow Traveller

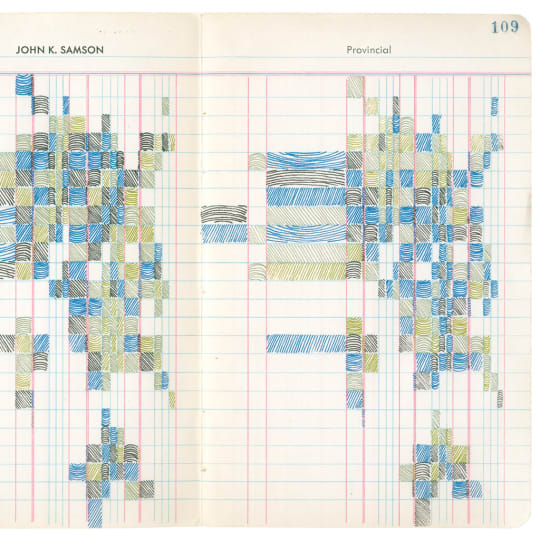

Winter Wheat, John K. Samson

Lyrics

“After his statement, Blunt, who is now 72, broke down in tears. Then he left the Times looking a lonely figure, and pursued by pressmen.”

—BBC Nine O’Clock News, November 20, 1979

Rain for the last day that I will be known the way that I want them to know me. Rain for reporters’ predictable leads on the darkening stain of my name. Rain, like the morning you left with the International Brigade, the streak of your face at the glass

when the train pulled away. The aspidistra that refused to die;

a miniature camera in a Cambridge tie; to get that Soviet control to crack a smile. All in our file, my fellow traveller. Sleep for the telephone’s silent receiver on its beetle-black back in the hall. Sleep for the bottle that rolled off my desk and danced itself out on the floor. Sleep for the overturned ashtray splayed across an unmade bed, while I interrogate every word that I ever said. I fall from buildings into angry air, lecture my students in my underwear, but once I was allowed to dream of you instead,

my dear defected fellow traveller—how you booked your final passage with a passport that you paid for with a pair of roller skates, how you dyed your hair and moustache, put on a Mid-Atlantic accent but you couldn’t stop the shakes when they asked where you had come from, and you muttered, “That’s a good one,” that you were “never really certain.” Every umbrella down on Portman Square opens and closes to arraign our fair theory of something I can’t picture anymore: a forgery for my fellow travellers. I won’t wait to see. I still believe in you and me. My fellow traveller.

Releases

Artist Bio

John K. Samson

Inspired by the search for connection and community, his hometown of Winnipeg, and our individual and collective struggles with addictions to drugs, screens, and fossil …

Contact

-

Official Site

www.facebook.com/johnksamsonmusic

-

Publicity

Christine Morales

-

Licensing

Hector Martinez

-

US Booking Agent

Frank Riley High Road Touring

-

EU Booking Agent

Grand Hotel van Cleef Musik

-

EU Label Contact

Alma Lilic

-

Australia Label Contact

Dave Jiannis

-

Canada Label Contact

Tonni Maruyama